The Government of Turkey launched a research vessel into the Aegean Sea on August 10, 2020. The vessel was set to do research on possible fossil fuel deposits in the Mediterranean. While its mission might have seemed innocuous to an outsider, the ship sailed directly into an international conflict of major proportions. The Turkish ship was searching for oil in waters claimed by Greece.

The Greek government and the European Union condemned the Turkish action, and Greece started preparing its military for war. France has sent ships and fighter jets to the Aegean to support Greece and is planning to sell one frigate (a type of warship) and 18 fighter jets to Greece. NATO-organized talks have broken down, and the two nations are currently in a tense standoff.

Fossil fuels are the current reason tensions between Greece and Turkey are high, but these countries have a millennium-long history with each other that plays into this crisis. The Greeks first encountered the Turks in the 11th century. At this time, the Greeks were the rulers of the Eastern Roman Empire, a nation which occupied much of what is much of what is now modern Turkey and the Balkans. Almost all of these areas spoke Greek.

In the year 1071, a group of Turks were migrating down from Central Asia. The Turks and Eastern Romans clashed in Eastern Anatolia, where the Eastern Romans were decisively defeated. This defeat led to the slow but steady loss of Anatolia, now known as the Turkish Peninsula, to the Turks. The most decisive loss was in when the Eastern Roman capital of Constantinople was taken by the Ottoman Empire, a Turkish nation, in 1453.

Slowly but surely, the Greek-speaking population of the Ottoman Empire was assimilated by the Turkish nobility. By the early 19th century, the remnants of a once-thriving Greek population only remained in a few small areas: what is now modern-day Greece, a small quarter of the city of Istanbul, and the city of Smyrna. This population chafed under Turkish rule, and the Greek peninsula won its independence in 1832. There were, however, still major Greek populations in the Ottoman Empire.

In the early 20th century, the Ottomans sided with the Central Powers in the First World War and were defeated by the British on multiple fronts. During the war, Greeks were forcefully deported away from the coasts and into the center of Turkey. During these deportations, many Greeks were killed and their property seized.

Following their defeat, the Ottomans were weak and divided, and Greece, despite having few resources to pursue a conflict, declared war on the Ottomans with the intention of liberating the trapped Greek population in the Ottoman Empire. The Greeks landed forces in Smyrna, a city mostly populated by ethnic Greeks, and moved to occupy most of the Aegean coastline.

The Ottoman Empire, however, was overthrown, and Turkey was now ruled by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, a veteran of WWI. Under Ataturk’s command, the Greeks were pushed out of Turkey. Greeks were killed by the thousands by Turkish soldiers.

“My great grandparents from both sides [of the family] came from that region,” Sophia Vourakis ’24 said, a Greek citizen herself. “My other grandmother’s parents had their house burned in the Greek genocide. Constantinople was a cultural center at the time, and they had to leave their cosmopolitan life and start over with no money, doing manual labor. It was a very difficult time for them.”

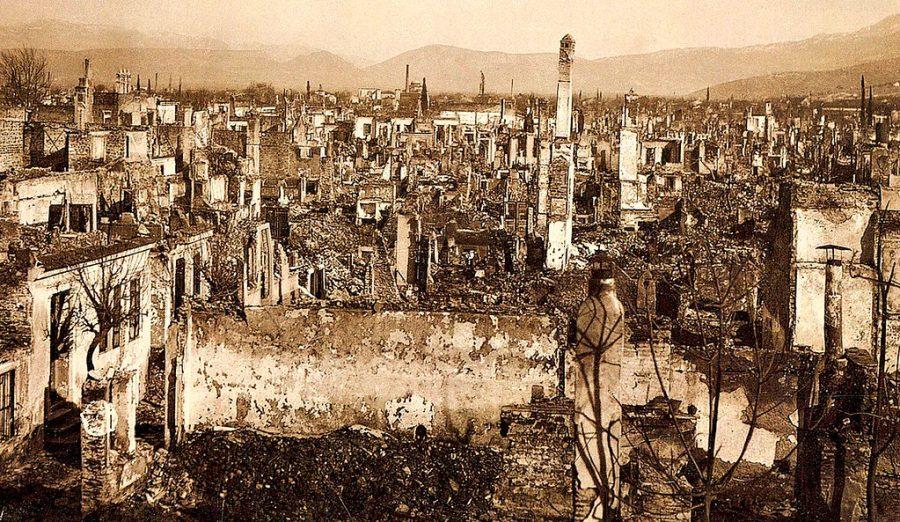

This genocide culminated in the Great Fire of Smyrna in 1922, where the Turkish military slaughtered tens of thousands of Greeks and deported the rest. This was one of the most significant acts of ethnic cleansing at the time, second only to the Armenian Genocide, which was perpetrated by the Turks a few years before; between 500,000 and 750,000 Greek civilians were killed. In 1923, the two nations agreed to the population exchange, where the majority of both Greeks and Turks in each nation were expelled and sent to their respective homelands.

“My great grandparents on my mother’s side were forced to leave everything behind in Serai, just outside Constantinople,” Vourakis said.

Later in the 20th century, another hotspot was Cyprus. Cyprus had a Greek majority and a Turkish minority. The British, however, controlled the island, keeping the balance between the groups. When the British left in 1960, this fragile balance collapsed. The Greek speaking government began to crack down on the rights of the Turkish minority, as well as the ethnic Greek paramilitary group EOKA B, which committed atrocities against the Turkish population. When Greece went through a coup in 1974, the new Greek government seeked to incorporate Cyprus into Greece. In response, Turkey invaded the island, pushed the Greeks out of the Northern portion of the island. The border remains tenuous today, with the self-declared, but not internationally recognized, Turkish Republic of North Cyprus occupying the Northern half of the island.

The Hagia Sophia is an Orthodox Christian cathedral built in the 6th century. It served as the seat of Eastern Orthodoxy for nearly 1000 years, but was converted to a mosque under Ottoman rule. When Ataturk took over Turkey in the early 20th century, he made it into a museum. It remained this way until July 10, 2020, when Turkey’s President allowed the museum to be once again turned into a mosque. The Hagia Sophia has become a symbol of rising tensions between the two nations. “It bothers me that the decision seems politically motivated,” said Vourakis, a Greek Orthodox herself. “Even from a purely historical or cultural perspective, it seems wrong to deprive people of the beauty and grandeur of this significant landmark in its original form.”

The relations between Greece and Turkey have stayed relatively stable for the last 100 years. There have been spats over Cyprus and other Aegean islands, but none of these became an all-out war. This dispute may be another one of these spats. If so, we can move on and continue the tense peace that has been present for the last century. However, each one of these spats has a side effect. It gives rise to nationalistic and religious extremist ideas, and poisons the relations between nations, and between people. At some point, these will boil over into bloodshed. This would not be the first time two peoples, two religions, two nations, with hundreds of years of shared history go to war. The possibility for a similar situation between Greece and Turkey is not as far away as you might think. “ History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes” Mark Twain said . If we do not understand the history between Greece and Turkey, and do not treat it for the time bomb it is, the blood will be on our hands when that time bomb explodes.